Long before the blockbuster movie, Black Panther blew up, earning more than $700 million at the box office in 2018 and sparking Black Panther parties (complete with regal costumes and the “Welcome to Wakanda” salutes offered in greeting)  and decades before African-Americans held our heads a bit higher and walked a bit taller on the day that Barack Obama was elected, there was another curious marker of African American pride. Oprah commented on it in a 2015 article in Page Six, and having experienced it firsthand, I can attest to the veracity of her words. There was a time, not so long ago, when black people were so hungry for positive images of ourselves that whenever a celebrity of color would grace the television screen, the old-fashioned land line with a 50-foot cord that hung on our kitchen wall would begin to ring “off the hook.” On the other end would be friends of my parents excitedly sounding the alert, “There are colored people on TV!” (Associated Press, 2015)

and decades before African-Americans held our heads a bit higher and walked a bit taller on the day that Barack Obama was elected, there was another curious marker of African American pride. Oprah commented on it in a 2015 article in Page Six, and having experienced it firsthand, I can attest to the veracity of her words. There was a time, not so long ago, when black people were so hungry for positive images of ourselves that whenever a celebrity of color would grace the television screen, the old-fashioned land line with a 50-foot cord that hung on our kitchen wall would begin to ring “off the hook.” On the other end would be friends of my parents excitedly sounding the alert, “There are colored people on TV!” (Associated Press, 2015)

At the risk of being labeled politically incorrect or even racist, please let me offer the standard disclaimer that “colored” was a perfectly acceptable, even polite term during my childhood in the 1960s. While I understand its problematic connotations, mainly the result of its use as a restrictive term during South African apartheid, I sometimes am actually a bit nostalgic for the word. It sounds so much happier than “black”, which always suggested anger and mourning to me and is much easier to say than the cumbersome “African-American” terminology favored today. The people of my race, both ordinary and celebrated, are “colorful”, in style, personality, and sheer range of differences among us and yet we happily complement one another, not unlike Crayolas in the coveted 24-box.

While white people, especially teenagers, may have called each other to alert the appearance of some specific popular entertainer (e.g. Elvis, The Beatles, or The Rolling Stones), for us it made no difference who the performer was. Little known comedians, like a very young (and surprisingly chaste) Richard Pryor making his debut on the Ed Sullivan Show garnered as much excitement as “A-Listers” like Ella Fitzgerald and Louie Armstrong. Performers brand new to the scene, like the iconic, yet futuristic 5th Dimension were celebrated in equal measure to more traditional singers like Della Reese and Harry Belafonte. What was the reason for the “colored people on TV” calling tree? Quite simply, the thirst among African Americans for positive self-imagery.

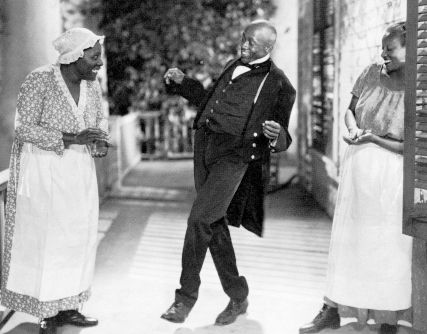

In the early days of first radio and then movies, black Americans were portrayed as either slightly shady characters or buffoons. From Amos and Andy on the radio (who were, interestingly, actually voiced by two white men, to Stepin Fetchit,  whose character was billed as the “laziest man in the world”, to the hysterical and high-voiced “Prissy” in Gone With the Wind, played by actress Butterfly McQueen, seemed designed, at best, to make black Americans the butt of every joke and, at worst to serve as proof of our inferiority, and therefore to justify the discrimination and ill treatment that regularly came our way. So, when talented, classy, well-dressed black performers graced our TV screens in those early days, it was truly cause for celebration.

whose character was billed as the “laziest man in the world”, to the hysterical and high-voiced “Prissy” in Gone With the Wind, played by actress Butterfly McQueen, seemed designed, at best, to make black Americans the butt of every joke and, at worst to serve as proof of our inferiority, and therefore to justify the discrimination and ill treatment that regularly came our way. So, when talented, classy, well-dressed black performers graced our TV screens in those early days, it was truly cause for celebration.

While there are some white Americans who, even today, feel that African Americans are “too sensitive” and should just “get over it” when it comes to discrimination, both past and present, there is actually scientific evidence that prejudice and discrimination can have detrimental effects on mental health. Perhaps the most famous was the Doll Experiment, conducted by married psychologists, Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark in which black children ascribed negative attributes to black dolls. Attorney Thurgood Marshall used the Clark’s results in his argument in the Brown vs. Board of Education case before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954 (National Park Service, 2015). More recently, however, a study of discrimination against Asian Americans, conducted by researchers at UCLA in 2007 also confirmed that “…when people are chronically treated differently, unfairly, or badly, it can have effects ranging from low self-esteem to a higher risk for developing stress-related disorders such as anxiety and depression…” (Gordon, 2016). I suspect that, at some, perhaps subconscious level, my parents and their friends realized the harm that could result from “invisibility” and, therefore, remained doggedly determined to witness any positive portrayal of our culture whenever the opportunity presented itself.

By the 1970s, as “colored people” gave way to “blacks”, the proliferation of black performers and sit-com characters brought the need for the excited prime-time phone calls to an abrupt end. Temporary blips of excitement, such as the mini-series, Roots in the late 1970s, the premiere of The Cosby Show in 1984, and the national debut of The Oprah Winfrey Show in 1986, notwithstanding, the appearance of minorities on television had become so commonplace that we quickly began to take it for granted. This was both good and bad in a way. There are many young African Americans who cannot remember a time when seeing a person of color on TV was so rare that its occurrence sparked a community-wide communication chain, and this, I think is definitely a plus. Programs such as Blackish and This Is Us,  which present African Americans as “regular people” can simply be enjoyed, by people of all races, as quality programming. The downside, however, is that there are a growing number of programs, many of them in the so-called “reality show” genre that are serving, once again, to reinforce negative stereotypes about people of color. Although apparently popular with viewers, programs such as The Real Housewives of Atlanta and Empire do little to dispel unflattering, stereotypical notions about African Americans. Even celebrated life coach, Iyanla Vanzant, whom I believe has a genuine desire to help individuals in crisis, often seems to unnecessarily showcase the most negative aspects of African American families on her show, Iyanla, Fix My Life on OWN.

which present African Americans as “regular people” can simply be enjoyed, by people of all races, as quality programming. The downside, however, is that there are a growing number of programs, many of them in the so-called “reality show” genre that are serving, once again, to reinforce negative stereotypes about people of color. Although apparently popular with viewers, programs such as The Real Housewives of Atlanta and Empire do little to dispel unflattering, stereotypical notions about African Americans. Even celebrated life coach, Iyanla Vanzant, whom I believe has a genuine desire to help individuals in crisis, often seems to unnecessarily showcase the most negative aspects of African American families on her show, Iyanla, Fix My Life on OWN.

With the advent of the Internet and social media, TV itself appears to be on an inevitable collision course with extinction. Nevertheless, it is my hope that someday, not only the world of popular media, in whatever form it will exist in the future, but the “real world” as well, will reflect true “reality”, which is that good and bad, smart and stupid, honest and shady, loving and evil as well as everything in between all exist within humankind as a whole. No race, or religion, or culture has completely cornered the market on either positive or negative traits. Wouldn’t it be great if we could recapture some of the positive excitement of the past by using SMS, Instagram, or Twitter to alert one another of the presence of positive examples of real people, no matter what their race or ethnicity?

Works Cited

Associated Press. (2015, May 14). Oprah Reflects on History of African-Americans on TV. Retrieved from Page Six: https://pagesix.com/2015/05/14/oprah-reflects-on-history-of-african-americans-on-tv/

Gordon, D. (2016, January 13). Discrimination Can Be Harmful to Your Mental Health. Retrieved from UCLA Newsroom: http://newsroom.ucla.edu/stories/discrimination-can-be-harmful-to-your-mental-health

National Park Service. (2015, April 10). Kenneth and Mamie Clark Doll. Retrieved from Brown v. Board of Educaton National Historic Site Kansas: https://www.nps.gov/brvb/learn/historyculture/clarkdoll.htm